Most athletes already know the mental side of sport matters. The part most athletes don’t know is whether it can actually be trained; whether it’s a skill you develop, or just something you either have or you don’t.

Picture this: you’ve trained for months. Fitness is sharp. Technique is dialled. You know exactly what you need to do.

Then the moment arrives. The penalty. The decisive race. The game you’ve been building towards all season. And something shifts. Your mind starts racing. Doubt creeps in. The body that moved so naturally in training suddenly feels like it belongs to someone else.

This isn’t a fitness problem. It isn’t a technique problem. It’s a mental performance challenge. And if you’ve competed at any level in any sport, you’ll know exactly what that feels like.

So, can it be trained? The answer is straightforward: it’s a skill. And like any skill, it can be developed.

What mental performance actually is

Mental performance is a specific thing. Not a buzzword, not a vague idea. It’s a defined set of trainable psychological skills that shape how you think, respond, and compete.

The Association for Applied Sport Psychology describes it as the work of helping athletes strengthen the ability to perform and the ability to thrive: reducing anxiety, improving concentration, building confidence, and setting meaningful goals. In plain terms, it’s the mental side of sport, made practical.

It’s worth clearing up two things it often gets confused with.

It’s not the same as mental health

Mental health is about your overall psychological wellbeing: things like depression, anxiety disorders, and burnout. Mental performance is about the skills that help you compete. The two are connected, and one affects the other, but they’re not the same thing.

You can have strong mental performance skills and still be going through a tough time mentally. You can also be in a good place mentally and still have a lot of work to do on your psychological skills as an athlete. Both deserve attention; they just need different kinds of it.

It’s not the same as “mental toughness”

Mental toughness is one of the most overused phrases in sport, and one of the most poorly defined. Researchers have literally described it as having a “definitional dilemma.” More importantly, when people use the phrase, they usually mean something you’re born with or you’re not.

That framing isn’t helpful, and it isn’t accurate. Mental performance skills, things like self-awareness, focus, emotional regulation, confidence, and resilience, can be taught, practised, and improved. That’s a fundamentally different idea, and it changes everything about how you approach your own development.

Sport psychologist Robin Vealey, one of the most respected figures in the field, puts it simply: mental skills are “learnable psychological capabilities.” Not fixed traits. Capabilities. Things you build.

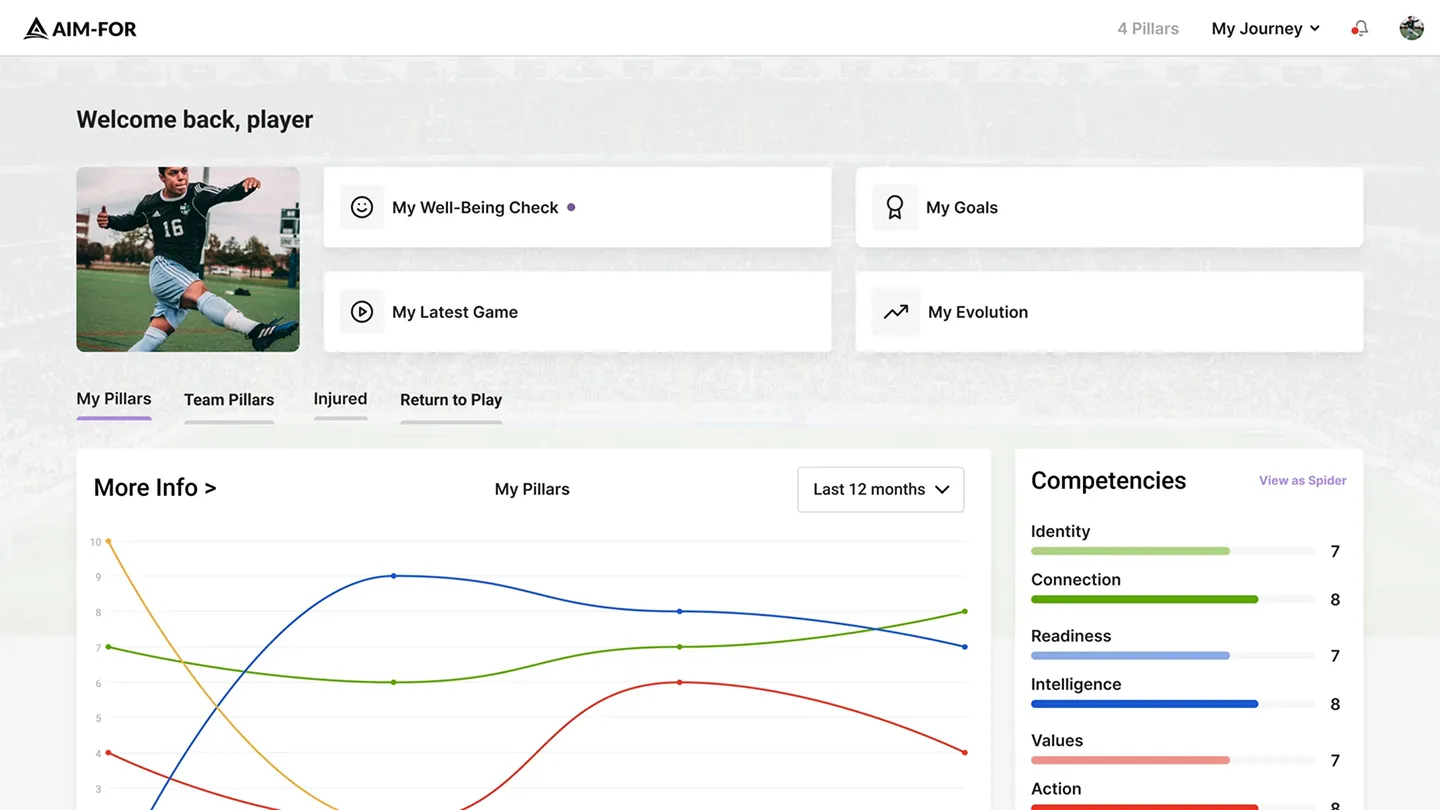

The thinking behind The 4Pillars

The 4Pillars model was developed by Lee Richardson, sport psychologist currently at Liverpool FC, having previously worked with England’s U19 national team and Premier League clubs West Ham United and Crystal Palace. Lee is also a former professional footballer and co-founder of AIM-FOR.

He built the framework from over two decades of applied work in elite sport, where lived experience meets academic knowledge, and it’s grounded in a straightforward idea: the mental demands athletes face are predictable, and because they’re predictable, they can be prepared for.

The model organises mental performance around four core components, or Pillars: Awareness, Attitude, Agility, and Adjustment. Each reflects something the research consistently identifies as central to how athletes perform under pressure.

Lee’s work led to a standardised psychoeducation programme being delivered across Premier League and EFL academies via the Professional Footballers’ Association, giving young professional players the psychological grounding to understand and navigate a professional career before the demands of that career overwhelmed them.

That programme was independently evaluated and published in the Scandinavian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Players and staff across 33 professional clubs rated it highly, describing the content as realistic, directly applicable, and genuinely useful in their day-to-day lives as athletes.

Download the full research paper →

Everything on this platform is built on the same principles: drawn from real sport, tested in elite environments, and grounded in evidence. That’s the foundation.

Why most athletes still don’t train it

Here’s something worth sitting with.

Ask most athletes what percentage of their performance comes down to the mental side, and they’ll say something like 50%, 60%, often higher. Ask the same athletes how much of their training time they actually spend on mental skills, and the number drops to almost nothing.

Weinberg and Gould, authors to one of the most widely used sport psychology textbooks in the world, describe this as one of the most common observations in the field. The gap between how much athletes think the mental side matters and how much time they give it is almost universal.

Part of it is structural. Mental skills don’t show up on a training schedule the way running drills or gym sessions do. There’s no obvious slot for them. Part of it is that mental performance is harder to measure than a sprint time or a max lift, so it’s easier to deprioritise.

But a big part of it is cultural. Sport has always carried a “toughen up” mentality: the idea that admitting you’re struggling mentally is a sign of weakness, that the strong just get on with it, that needing help is something to be embarrassed about. Research backs this up: a 2023 meta-analysis found that fewer than one in four athletes with mental health difficulties sought formal help. In English professional football, a 2024 survey found that around half of clubs didn’t have a sport psychologist on staff.

That’s a significant gap. And it has real consequences, not just for athletes’ wellbeing, but for their performance. Unaddressed anxiety, poor emotional regulation, and eroded confidence don’t just make you feel worse. They directly undermine the physical performance you’ve put thousands of hours into developing.

The pressures that come with being an athlete

Mental performance training isn’t about fixing something broken. It’s about preparing for the specific pressures that come with competing. Pressures that are predictable, recurring, and largely the same regardless of what sport you play.

Performance Anxiety

The ability to access what you’ve trained for when the stakes are highest is what separates consistent performers from those who go hot and cold. The IOC’s 2019 consensus statement on athlete mental health, one of the most authoritative documents in the field, confirmed that psychological symptoms directly impair performance. It’s not a side issue. It’s central to results.

Injury

The physical side of injury is well understood and well managed. The mental side often isn’t. The PFA’s most recent wellbeing survey found that 68% of professional footballers said fear of injury was the single biggest factor affecting their mental wellbeing.

Research by Gouttebarge and colleagues found that athletes with serious time-loss injuries were two to four times more likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depression. The rehabilitation programme accounts for the knee or the shoulder. It rarely accounts for the doubt, the fear of re-injury, or the identity loss that comes with being unable to do the thing that defines you.

Loss of form

Every athlete goes through it. The danger isn’t the dip itself. It’s what happens in your head during it. When confidence drops and self-doubt fills the gap, form slumps can become self-reinforcing. Without the tools to understand what’s happening, what should be a temporary rough patch can drag on far longer than it needs to.

Deselection and rejection

These hit harder than people outside sport tend to appreciate. A study of elite adolescent soccer players found that those who were deselected experienced clinical levels of psychological distress, significantly higher than players who were retained. For a young athlete who has invested years of their life in pursuit of a goal, being told they haven’t made it isn’t just disappointing. It can feel like losing part of who they are.

Transitions

Moving from youth to senior, from amateur to professional, from one club or programme to another: these are among the most psychologically demanding periods in an athlete’s career. Research suggests that only 20–30% of athletes navigate the junior-to-senior transition well on their own. The shift isn’t just environmental. It requires a complete recalibration of identity, expectations, and self-belief.

Retirement

Between 18% and 39% of retired elite athletes experience clinically significant symptoms of depression or anxiety, and the figure is higher for those whose retirement was involuntary, through injury or being released.

Park, Lavallee, and Tod’s widely cited systematic review found that around 16% of transitioning athletes experienced serious adjustment difficulties, including grief and a deep sense of identity loss.

Retirement from sport is one of the most significant psychological transitions a person can go through. It’s still one of the least supported.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re the normal landscape of a sporting career. Mental performance training exists to prepare athletes for exactly this.

The skills that actually make the difference

The good news is that the skills involved are well understood, well researched, and genuinely trainable. Here’s what the evidence says about the ones that matter most.

Self-awareness

Self-awareness is where everything starts. If you don’t know how you think under pressure, what triggers your anxiety, or what happens to your performance when your confidence drops, you can’t do anything about it. It’s not about being self-absorbed. It’s about understanding your patterns well enough to work with them rather than against them.

Self-talk

Self-talk might sound basic, but the research is significant. A meta-analysis by Hatzigeorgiadis and colleagues (2011) across 32 studies found a meaningful positive effect on performance. It works because it sharpens focus, helps regulate effort, and gives you a way to manage your emotional state in the moment. Not suppress it, manage it. Like any skill, it improves with deliberate practice.

Imagery and visualisation

Imagery and visualisation have decades of evidence behind them. A 2025 meta-analysis of 86 studies involving more than 3,500 athletes confirmed that structured imagery practice improves performance. The sweet spot is around ten minutes a session, three times a week, sustained over time, and it works best when combined with other mental skills rather than used on its own.

Emotional regulation

Emotional regulation is the ability to stay composed, or to recover composure quickly when you lose it. This isn’t about switching off your emotions. Intensity, drive, and competitive energy all have their place. The goal is to understand your emotional responses well enough that they work for you, not against you.

Focus and attentional control

Staying present in a performance rather than drifting into past mistakes or future anxieties is one of the clearest differences between elite and sub-elite athletes. Research by Mann and colleagues (2007) found that elite athletes make significantly better use of the information available to them: sharper anticipation, better pattern recognition, calmer decision-making under pressure. Those differences don’t come from talent. They come from practice.

Resilience

The ability to respond well when things go wrong is probably the most misunderstood skill on this list. It’s often talked about as if it’s a personality trait you either have or you don’t. But a landmark study of ten US Olympic gold medallists by Gould, Dieffenbach, and Moffett (2002) found something different.

The psychological qualities that defined those athletes, things like coping with pressure, maintaining focus through adversity, and setting meaningful goals, had been developed over time. They weren’t born with those qualities. They built them.

The overall evidence for psychological skills training is clear. Brown and Fletcher’s (2017) meta-analysis, the most rigorous in the field covering 35 randomised controlled trials, found that psychological interventions produced a meaningful positive effect on sport performance, with those gains holding at follow-up a month later.

This isn’t marginal. It’s the difference between performing at your best and leaving it in the training ground.

Enjoying this post?

If you're finding this post helpful, get more mindset insights and tools from the 4Pillars team, straight to your inbox.

You’re not born mentally strong. You develop it.

This is probably the most important thing in this article, so it’s worth saying plainly.

The idea that psychological strength is fixed, that some athletes have it and others don’t, is one of the most damaging myths in sport. It stops athletes from investing in their mental development. It gives coaches an excuse not to address it. And it isn’t true.

Vealey’s 2023 framework describes mental skills as “learnable psychological capabilities.” Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Römer’s foundational research on expertise established that elite performance, including its psychological dimensions, is explained primarily by acquired characteristics developed through deliberate practice, not innate talent.

The mental edge elite athletes have isn’t something they were born with. It’s something they built, often without even realising that’s what they were doing.

Carol Dweck’s work on growth mindset, applied directly to sport, found that athletes who believed their ability came from effort and practice outperformed those who believed it was fixed, over the course of a full season. A 2025 study confirmed a strong positive relationship between growth mindset and competitive motivation.

Neuroscience backs it up too. Research by Herold and colleagues found that sustained practice produces measurable structural and functional changes in the brain. The same way your muscles adapt to consistent physical training, your brain adapts to consistent mental work. That’s not a metaphor. That’s biology.

What this means practically: if you’ve been telling yourself you’re just not mentally strong, you’ve been describing a starting point, not a permanent state. Mental performance is trainable. It can be planned for, practised, and tracked, the same way every other part of your game can be.

There’s also a protective side to getting this education early. Athletes who understand the psychological demands of their sport before they hit them, the identity pressures, the impact of injury, the emotional weight of transitions, are much better placed to manage those experiences when they arrive. Knowledge is preparation.

The research on psychoeducation is consistent: structured psychological education, delivered early, produces better outcomes across the full arc of an athletic career.

Identity: the thing nobody talks about enough

There’s one part of mental performance that doesn’t get the attention it deserves, and it underpins all the rest: identity.

Athletic identity is how strongly you define yourself through being an athlete. Research across thousands of athletes shows that strong athletic identity brings real benefits: higher motivation, stronger commitment, deeper engagement with your sport.

But it carries significant risks when it’s the only identity you have. Researchers describe this as identity foreclosure: pouring everything into the athlete role without developing any sense of who you are outside it. When that role gets threatened, through injury, deselection, a loss of form, or retirement, there’s nothing to fall back on. The loss can feel total.

A 2025 study by Claes and colleagues found that athletes who ruminated on their identity without resolution experienced higher rates of injury, depression, and lower performance levels. The ones who fared better were those who had developed a broader sense of self.

The research is consistent: athletes who have an identity that extends beyond sport are more resilient across setbacks, across transitions, and across the end of their career. Identity work isn’t separate from performance work. It’s part of it.

Where to start with mental performance training

There’s no single entry point that works for everyone, but a few principles hold across sport, level, and age.

Observe yourself honestly

Before you can develop any mental skill, you need to know what’s actually going on in your head, not what you think should be going on. A simple habit of reflecting on your mental state after training and games, not just your physical output, will tell you more than you might expect.

Build mental work into your routine, not your crisis response

The biggest mistake athletes make is only thinking about the mental side when something has gone wrong. Pre-performance routines, self-talk strategies, imagery work: these are most effective when they’re part of how you prepare every day, not something you reach for when you’re already struggling.

Get the education before you need it

The athletes who handle the hard moments best are usually the ones who understood those moments were coming. Learning how performance anxiety works, what identity disruption feels like, why transitions are psychologically demanding, before you’re in the middle of them, gives you a framework to make sense of your experience when it happens.

Be patient

Mental skills develop at the same pace as physical ones. Composure, confidence, and focus don’t transform overnight. They’re built through consistent practice and honest reflection over time. That’s not a limitation. It’s just how development works.

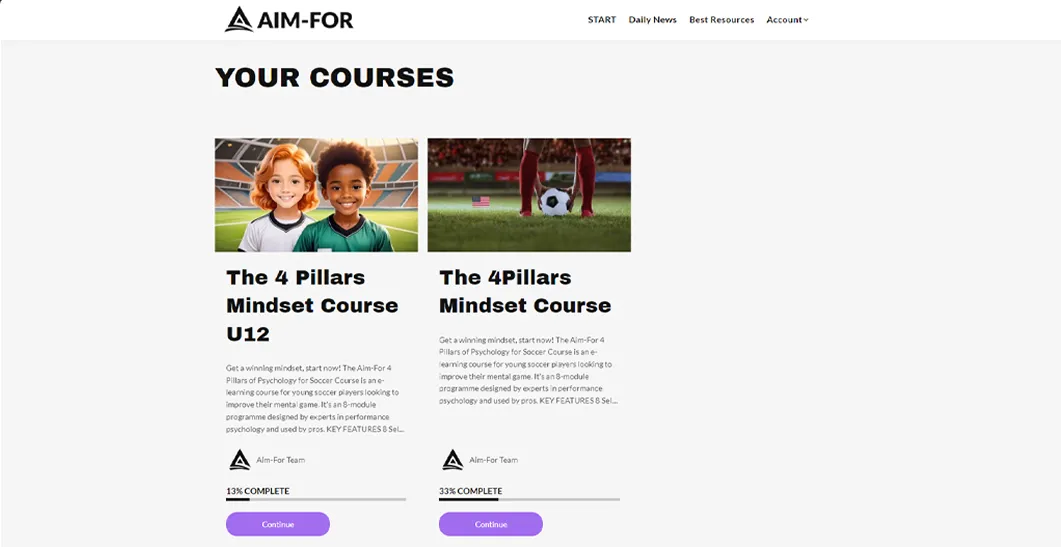

A structured way to develop your mental performance

For athletes who want a structured, evidence-based way to actually develop these skills, not just read about them, The 4Pillars Courses were built for exactly that.

Every course is developed by Lee Richardson and grounded in the Four Pillars© Psychological model: the same framework validated through peer-reviewed research and used inside professional sport. The content is practical, sport-specific, and designed to be worked through at your own pace.

Courses are available for soccer players and cricketers across all age groups.

Explore The 4Pillars Courses →

Sources

- Vealey, R.S. (2023). Mental skills framework. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 36(2), 365–384.

- Richardson, L., Lugo, R., and Firth, A. (2022). Investigating an Online Course for Player Psychosocial Development in Elite Sport (Professional Football). Scandinavian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4(1), 10–19.

- Reardon, C.L. et al. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 667–699.

- Gouttebarge, V. et al. (2019). Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 700–706.

- PFA Wellbeing Survey (2023/24). Professional Footballers’ Association.

- Blakelock, D.J., Chen, M.A., and Prescott, T. (2016). Psychological distress in elite adolescent soccer players following deselection. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 10(1), 59–77.

- Park, S., Lavallee, D., and Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: a systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 22–53.

- Hatzigeorgiadis, A. et al. (2011). Self-talk and sports performance: a meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(4), 348–356.

- Imagery meta-analysis (2025). 86 studies, 3,593 athletes. PMC/National Library of Medicine.

- Mann, D.T.Y. et al. (2007). Perceptual-cognitive expertise in sport: a meta-analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(4), 457–478.

- Gould, D., Dieffenbach, K., and Moffett, A. (2002). Psychological characteristics and their development in Olympic champions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(3), 172–204.

- Brown, D.J. and Fletcher, D. (2017). Effects of psychological and psychosocial interventions on sport performance: a meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(1), 77–99.

- Ericsson, K.A., Krampe, R.T., and Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

- Dweck, C.S. (2009). Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Olympic Coaching Magazine.

- Herold, F. et al. (2019). Functional and structural changes following sport and exercise training. Frontiers in Psychology.

- Brewer, B.W., Van Raalte, J.L., and Linder, D.E. (1993). Athletic identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles heel? International Journal of Sport Psychology, 24, 237–254.

- Claes, L. et al. (2025). A Multidimensional Perspective on Athletic Identity in Competitive Athletes: Associations With Sociodemographic and Sport‐Specific Variables and Psychological Symptoms. European Journal of Sport Science, 25(7).